The story of Musium

written by Ruud van Asseldonk

published

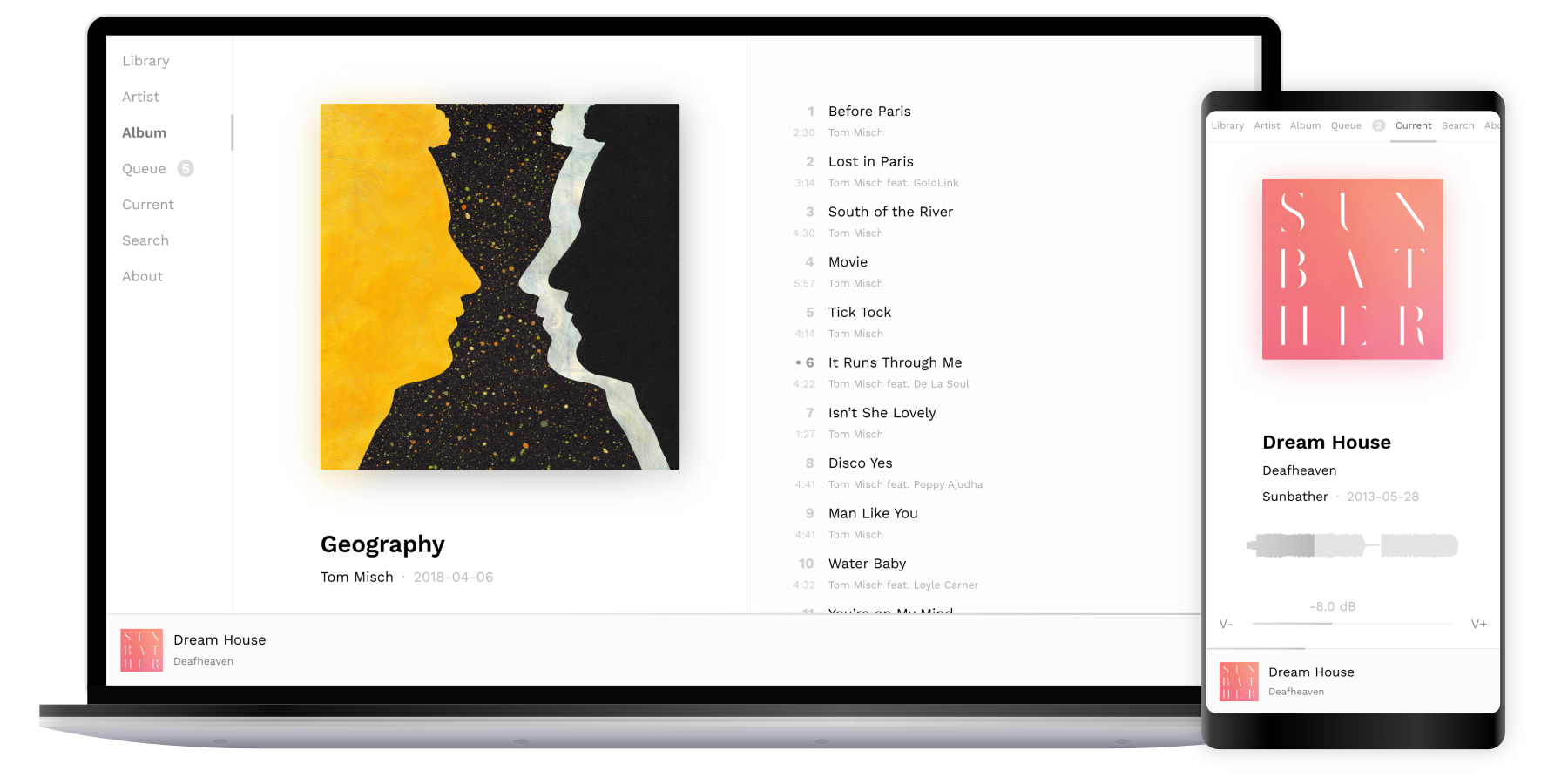

Musium is the music player that I built for myself. It runs on a Raspberri Pi that connects to the speakers in my living room, and I can control it from my local network using a webinterface. I’ve been using it on a daily basis for years, but it’s far from finished. In some areas it’s very polished, but implementing pause and skip is something I haven’t gotten to yet.

Musium is my ultimate yak shave. It’s NIH’d across the stack. It uses my flac decoder, and I implemented the loudness analysis, normalization, and high pass filter. The application is built around a custom in-memory index. It persists data to SQLite, for which I wrote a code generator that generates Rust bindings for SQL queries, and the frontend is written in PureScript using my own html builder library. I take joy in getting the details right: the seek bar is not just a line, it renders a waveform, and the UI is animated throughout. Musium tracks fairly elaborate statistics about playcounts, so it can surface interesting music at the right time, and I developed a new shuffling algorithm for it. Not only is it a lot of fun to build, Musium does exactly what I want it to do, and that’s very satisfying. As an entry for the Lobsters blog carnival, this is its story.

The flac decoder

Back in 2014, Rust started to regularly show up in my news feed. It got many things right that frustrated me in other languages at the time, and I was eager to learn. I started by porting a path tracer, but what was a good next project? What’s a good fit for a low-level memory-safe language? Codecs. ClusterFuzz did not exist, and I regularly had media players segfaulting on corrupted files. I figured that a video codec would be too ambitious, but audio should be feasible.

I already had a collection of flac files, so I wrote Claxon, a decoder for the codec. In a world where content can disappear from streaming services at any time, I find it reassuring to have files on a disk that I control, and to maintain my own software that can decode them. Nobody can take that away.

In order to test Claxon and play back the decoded samples, I also had to write Hound, a library to read and write wav files. This was the early days of the Rust ecosystem, and no library for that existed at the time! It was pre-1.0, and just before Rust did an invasive refactor of IO in the standard library — a move that Zig would go on to popularize 10 years later.

So I had my flac decoder, but aside from the fun of writing it, I didn’t have a direct use case for it. At that time, I wasn’t planning to write a music player.

Chromecast and the metadata index

A few years later I was temporarily renting a furnished apartment, and it came with a multi-room Sonos system. Until then, at home I mostly listened to music from my PC. Having music in every room was an amazing new experience, and I needed to have this at home when I moved back. Sonos was expensive though, and the app was unreliable.

Then there was Chromecast Audio. In theory, it was perfect. It played flac, supported multi-room audio, and I could control it from my phone. I could even get an employer discount on it, so I bought three of them. But Chromecast was not a full solution. It streams media over http, but something external needs to trigger playback; it doesn’t come with a library browser itself.

So that’s what I set out to build: an http server that could serve my flac files, with a library browser that would enqueue tracks on the Chromecast. I had Claxon that could parse tags from flac files, and I built an application on top of it that would traverse my files at startup, read their metadata, and build an in-memory index that it would serve as json. I intended to run this on a Raspberry Pi, so I wanted my code to be efficient — before generation 3 these things were slow, and memory was counted in megabytes. All of this was a premature optimization, but it was fun to build!

At the time SSDs were still quite expensive, so I kept my library on a spinning disk. Optimizing disk access patterns was a fun journey. Reading a few kilobytes of 16k files benefits enormously from a deep IO queue, because the head can sweep across the disk and serve many reads along the way. By bumping /queue/nr_requests in /sys/block, and reading with hundreds of threads, indexing 16k files with a cold page cache went down from 130s to 70s.

Now I had a server that could serve my library, and I could even start tracks with rust-cast, but that’s still not a music player. I needed a UI.

Adding a webinterface

I wanted a library browser that I could use from my phone, as well as desktop. I considered various ways to build an Android app, as well as a web app. None of them were great. A native Android app would not easily run on my desktop. Flutter was the new hot thing, but its opinionated tooling was incompatible with Nix, and I didn’t want to spend more time fixing my development environment every few months, than writing code. I gravitated back to web after all, but JavaScript is unsuitable for anything over a few hundred lines of code, and TypeScript had a dependency on the NPM and nodejs ecosystem for which I have a zero-tolerance policy in my personal projects. (I’m excited for typescript-go, but it did not exist at the time.) Fortunately, Elm and PureScript required no NPM or nodejs. I started with Elm, but I found it too constraining in how it interacts with JavaScript, which I needed to do to use Cast. So I switched to PureScript. If Elm is Haskell for frontend developers, PureScript is frontend for Haskell developers. PureScript stuck.

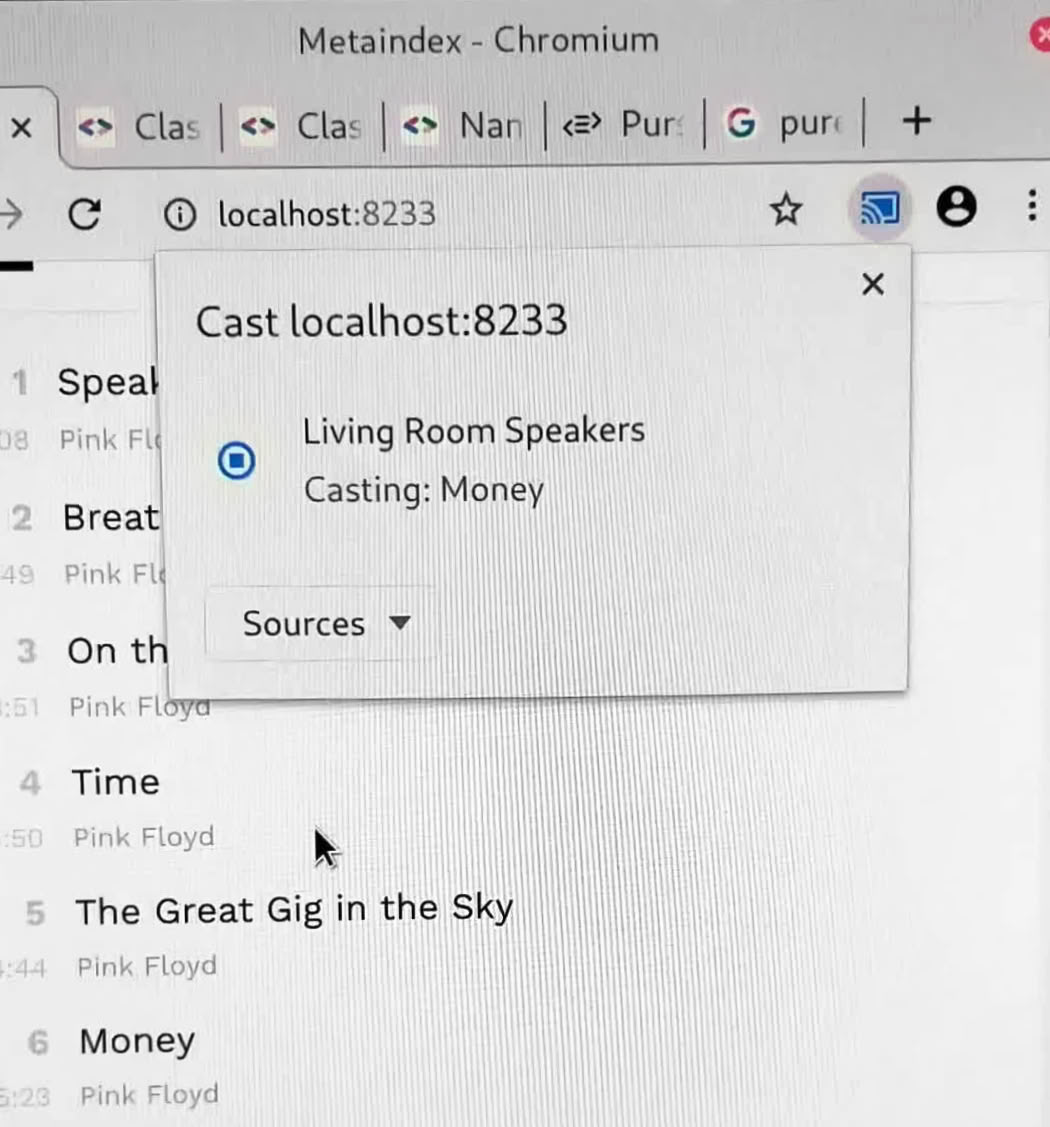

In July 2019, for the first time I was able to cast a track from my web app using the Cast API that Chromium exposes. Above is a frame from a video I took at the time.

I’ll build my own frontend framework

I did really like Elm’s approach to defining DOM trees, similar to blaze-html in Haskell. The PureScript counterpart of that was Halogen, so that’s what I started out with, but I struggled to build what I wanted. Halogen’s model where an application is a pure function State -> Html works well when all changes are instant, but that’s not what I wanted to do. In the browser, DOM nodes have state like selections and CSS transitions. It was not enough to give a declarative specification of the DOM tree, and let a library apply the diff between the current and new tree, I needed control over the nodes. Maybe I was holding Halogen wrong, but I decided to write my own DOM manipulation library instead, and I’ve been very pleased with it ever since. I later used it in my plant watering tracker as well. Here’s a small example, simplified from the way the volume slider is built:

type VolumeControl = { valueSpan :: Element }

volumeControl :: Decibel -> Html VolumeControl

volumeControl (Decibel currentVolume) = Html.div $ do

Html.addClass "volume-control"

Html.text "Volume: "

valueSpan <- Html.span $ do

Html.text $ show currentVolume <> " dB"

ask

pure { valueSpan }It feels declarative, and it preserves this workflow where rendering is a function from state to DOM nodes. If you look closely though, it’s imperative. Html is a reader monad that stores the surrounding node. Functions like div and span construct a new node, run the body with that node as context, and finally call appendChild to add the new node to its parent. We can use this approach to rebuild the entire tree, but with ask we can also store the node, and apply more targeted mutations later:

updateVolume :: VolumeControl -> Decibel -> Effect Unit

updateVolume control (Decibel currentVolume) =

Html.withElement control.valueSpan $ do

Html.clear

Html.text $ show currentVolume <> " dB"This library is now six years old, and I’m still very happy with the approach. Every time I need to edit the UI, I’m surprised by how easy it is to change.

Friendship ended with Chromecast

I was using Google Cast using the Web Sender API in Chromium, but it was very clear that this API was severely neglected. Many features were missing compared to the Android version, or outright broken. On top of that, the Chromecast would randomly disconnect or disappear from my network. I occasionally use apps on my phone to cast to my speakers, and sometimes it just stops playing, or suddenly switches from cast playback to the phone speaker. Chromecast is possibly the most unreliable software I’ve ever used. Building a music player on top of it was not going to work.

At that point, I decided to just play sound from the daemon instead. I bought a USB audio interface, connected it to the Raspberry, and my speakers to the audio interface. It’s not multi-room audio, but at least it works. It wasn’t my intention from the start, but now my server was no longer serving just files and metadata, it had become a mediaserver similar to MPD and Mopidy.

Toying around

Mopidy exists, why continue to build a music player? Well, it’s a lot of fun, and a good way to learn and experiment. But most of all, when you build your own software, you understand completely how it works, and you can add exactly the features you want, and make them work exactly the way you like. Some of the features that I added to Musium:

A pre/post playback hook. Musium can execute a program before starting playback, and after a period of silence. I use this with Ikea Trådfri outlets and coap-client to turn my speakers on when I start playback, and turn them off afterwards.

Last.fm scrobbling. Last.fm has my full listening history since 2007. Arguably that’s before I even developed any taste in music. It helps me discover new music, and I find it interesting to look at trends over time. This couldn’t stop now, so it’s one of the first features I added. Later I added importing as well. This ensures that I have a backup of the data in a place that I control. It also enables Musium to import playcounts from other devices, though that part has been sitting in an unmerged branch for a while.

A high-pass filter. My speakers can reproduce low frequencies, and my living room is almost square, which means bass notes start to resonate. Especially with 2020s music, if I turn up the volume, it quickly starts sounding dense, and I worry that I’m disturbing the neighbors. At some point I want to properly measure the room response and correct for it. Until then, a high-pass filter at 55 Hz does wonders.

Search as you type. Musium keeps indices that contain the words that occur in artist names, album titles, and track titles. I normalize the words, so I can type ‘royksopp’ or ‘dadi’ and find Röyksopp and Daði Freyr. Search searches all these indices for prefix matches, so with a single search box I can search for artists, albums and tracks. It ranks the results based on match properties (the length of the prefix for prefix matches, but also how common the word is in the library, the position of the word in the title, and a few others). This works extremely well: I can usually find what I’m looking for in just a few keystrokes, and a query runs in milliseconds, so search as you type feels instant.

Dominant color extraction. When you search or scroll through the library, that causes different cover art thumbnails to become visible. Even when those images are cached by the browser, it has to decode them, and this takes time, which causes flicker. For scrolling I solve this by creating the <img> nodes already for thumbnails that will soon scroll into view, but for search we can’t predict what will be visible next. To mitigate that, I compute a dominant color for every album cover, which is used as a fallback. This makes the flicker much less jarring: see a comparison here.

Playcounts, discovery, and recommenders

When I was younger, I could just remember which tracks on an album were the good ones. Unfortunately I’m not at an age any more where my brain just remembers anything I feed it, and as my library slowly grows, I increasingly struggle to find the right tracks. I added the ability to rate tracks, which helps to pick tracks from an album, but it doesn’t help me find albums in the first place. To help with that, I added various sorting modes to the album list.

Musium tracks exponentially decaying playcounts for every track, album, and artist. It does this at multiple time scales, to get a sense of what’s popular in the past weeks, months, and years. This powers a “discover” sorting mode, which surfaces albums that were popular in the past, but not played recently. The counters are rate-limited: if I listen to a full album with 10 tracks, and then a full album with 12 tracks, that second one should not be 20% more popular.

Music is very seasonal for me. Warm summer nights call for Com Truise or Roosevelt, on rainy autumn days I listen to A Moon Shaped Pool. On Saturday mornings I want chillout and jazz, on Friday evenings I want energetic drum and bass. To capture that, Musium tracks a time vector for every album: a 6-dimensional embedding that encodes the time of the day, day of the week, and day of the year at which listens happened. It uses this to rank albums in a “for now” sorting mode, and it’s weighed into the discover mode as well. This feature works amazingly well in practice.

Something I’m currently playing with is learning embedding vectors from my listening history, similar to word2vec. My hope is that it learns to cluster music that goes well together, so it can suggest related albums when I’m building a playlist. I’m not sure if just my own listening history is sufficient for that, but the power of gradient descent is remarkable. I tried this idea back in 2018, but couldn’t get it to work, and abandoned it. Now that transformers have demonstrated their power I wanted to try those, but I didn’t even need to. This time, with an embedding dimension of just 35, my much simpler model overfitted, and memorized the entire 40k-track history I trained it on. There is no neural network here! This is just minimizing the cosine distance between a weighted sum of the past 300 listens, and the 12k distinct tracks in the history! With a dimension around 10–15, so far it mostly learns to cluster music that I listened to in the same time period, which makes sense, but it’s not learning genres like I hoped. I have more ideas I want to try here, and bringing in more data from other ListenBrainz and Last.fm users is also an option. Either way, it’s a nice problem for building more intuition for machine learning.

Inventing wheels is fun!

I didn’t plan for it from the start, but over the past 11 years, I ended up building my own music player, that works exactly the way I want. It’s a great side project because it’s so diverse. I get to work with audio and digital signal processing. I get to implement database-like components like index data structures and full text search. There are opportunities for low-level optimization, but also to work on user interfaces and design. There are interesting math and machine learning problems.

Musium is also a great source of inspiration and test bed for other tools I build. The tediousness of using SQLite from Rust was the driving motivation behind Squiller, my tool that generates bindings for SQL queries. I now use it in several other projects too, and although it’s beta quality at best, I’m very pleased with the experience. The lexer and parser in Squiller were a refinement of the ones I wrote for Pris, so by the time I built RCL, I was pretty fluent in writing lexers and parsers. The frontend library came in handy for Sempervivum — my plant watering tracker that I use on a daily basis — and improvements I made there fed back into Musium. And although Musium persists its data in SQLite, the library and queries were a great dataset to test Noblit, my toy database.

And if I ever get bored with all that, there is still the pause feature I need to implement.