Writing a path

tracer in Rust

Part VII

Conclusion

written by Ruud van Asseldonk

published

As a learning exercise, I have ported the Luculentus spectral path tracer to Rust. The result is available on GitHub. In the process, I have also refreshed Luculentus a bit, updating it to modern C++. You can read about the details in the previous posts. In this post, I want to outline the process, and compare the final versions.

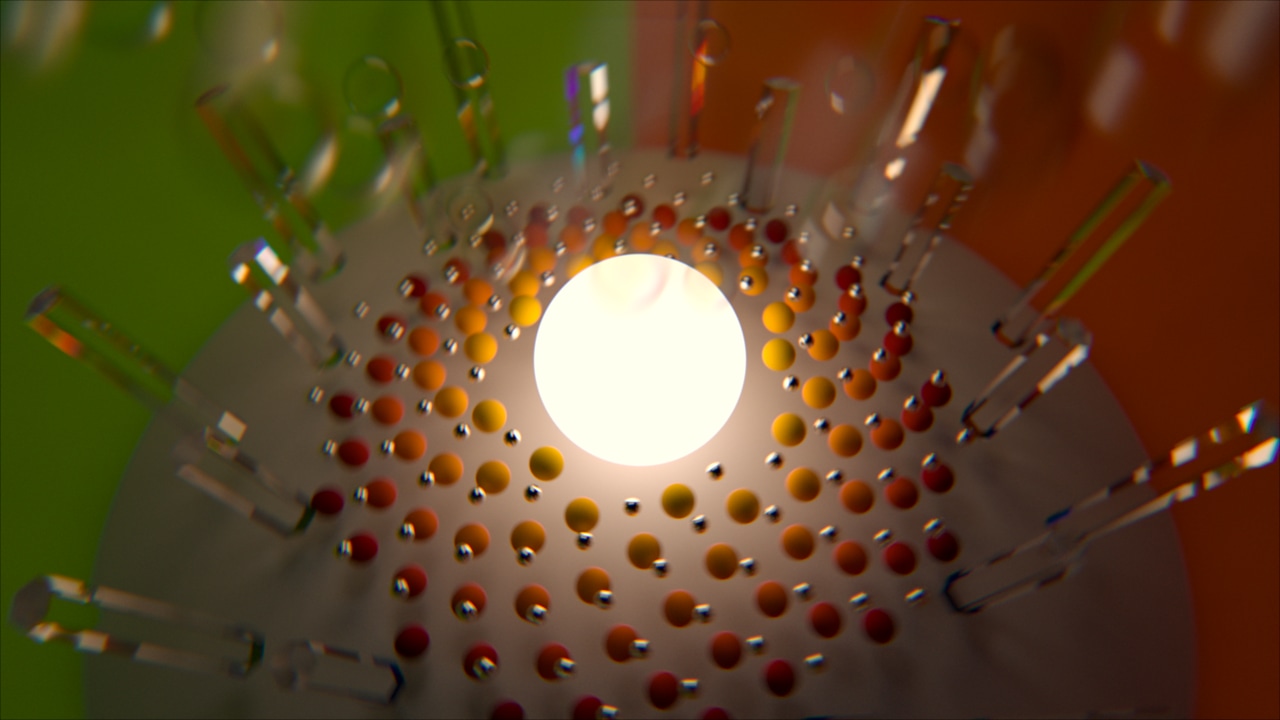

Eyecandy

First of all, the output of the path tracer! The scene is hard-coded, and it looks like this:

If you want to play with it, take a look at set_up_scene in app.rs.

Getting started with Rust

You can install the Rust compiler and Cargo within minutes nowadays, even on Windows. It was much easier to get this working than e.g. Scala with sbt.

I have found the Rust community to be very nice. When I did not know what to do, the IRC channel helped me out, and the subreddit was very useful as well. The core team is around there as well, so an answer from the experts is not uncommon.

At this point, Rust is a fast moving target. During the porting process, a handful of functions has been deprecated, functions have been renamed, and even bits of syntax have changed. Some people describe Rust today as a different language than it was a year ago, but I have not been using it long enough to experience that. Ultimately all changes should make the language better and more consistent, and I am confident that Rust 1.0 will be a great language.

Ownership

If I had to describe Rust in one word, it would be ownership. For me, this is the one thing that sets Rust apart from other languages. In most languages, ownership is implicit, and this leads to several kinds of errors. When a function returns a pointer in C, who is responsible for freeing it? Can you answer that question without consulting the documentation? And even if you know the answer, it is still possible to forget a free, or accidentally free twice.

This problem is not specific to pointers though, it is a problem with resources in general. It may seem that garbage collection is a good solution, but it only deals with memory. Then you need an other way to free non-memory resources like a file handle, and all problems reappear. For example, the garbage collector in C# prevents use after free, but there is nothing that prevents use after dispose. Is an ObjectDisposedException that much better than an access violation? Due to explicit lifetimes and ownership, Rust does not have these kinds of errors.

A static type system prevents runtime type errors that can occur in a dynamically typed language, but it has to be more strict at compile time. Rust’s ownership prevents runtime errors that can occur due to incorrect resource management, but it has to be even more strict at compile time. The rigorous approach to ownership makes it harder to write valid code, but if the compiler refuses to compile your code, there often is a real problem in it, which would go unnoticed in languages where ownership is implicit. Rust forces you to consider ownership, and this guides you towards a better design.

Updating Luculentus

The benefits of ownership are not specific to Rust. It is perfectly possible to write similar code in modern C++, which is arguably a very different language than pre-2011 C++. When I wrote Luculentus, C++11 was only partially supported. There were lots of raw pointers that are nowadays not necessary. I have replaced most raw pointers in Luculentus with shared_ptr or unique_ptr, and arrays with vectors. As a consequence, all manual destructors are now gone. (There were six previously.) Before, there were eleven delete statements. Now there are zero. All memory management has become automatic. This not only makes the code more concise, it also eliminates room for errors.

Porting the path tracer to Rust improved its design. If your resource management is wrong, it is invalid in Rust. In C++ you can get away with e.g. taking the address of an element of a vector, and when the vector goes out of scope, the pointer will be invalid. The code is valid C++ though. Rust does not allow shortcuts like that, and for me it has opened my eyes to an area that I was not fully aware of before. Even when working in other languages, if a construct would be illegal in Rust, there probably is a better way.

Still, the update demonstrates that it is possible to write safe code in modern C++. You do get safe, automatic memory management with virtually no overhead. The only caveat is that you must choose to leverage it. You could use a unique_ptr, but you could just as well use a raw pointer. All the dangerous tools of the ‘old’ C++ are still there, and you can mix them with modern C++ if you like. Of course there is value in having old code compile (Bjarne calls it a feature), but I would prefer to not implicitly mix two quite different paradigms, or keep all the past design mistakes around. It takes some time to unlearn using new and delete, and even then, old APIs will be with us for a long time.

A fresh start

A nice thing about Rust is that it can start from scratch, and learn from the mistakes of earlier languages. C++11 is a lot better than its predecessor, but it only adds features, and every new feature cannot break old code. One point where this shows is syntax. In Rust, types go after the name, and a return type comes after the argument list, which is the sensible thing to do. Rust’s lambda syntax is more concise, and there is less repetition. I still cannot get used to the Egyptian brackets though. They look wrong to me.

Another area where I think Rust made the right choice, is mutability. In Rust, everything is immutable by default, whereas in C++ everything is mutable by default. The Luculentus codebase has 535 occurences of const at the moment of writing. Robigo Luculenta has only 97 occurences of mut. Of course there is more duplication in C++, but this still suggests that immutable is a more sensible default. Also, the Rust compiler warns about variables that need not be mutable, which is nice.

Although syntax is to some extent a matter of preference, there are quantitative measures as well. If I compare the number of non-whitespace source characters, the C++ version has roughly 109 thousand characters — excluding the files that I did not port — whereas the Rust version has roughly 74 thousand characters, about two thirds the size of the C++ version.

C++ is notorious for its cryptic error messages when a template expansion does not work out. Rust’s errors are mostly comprehensible, but some can be intimidating as well:

error: binary operation `/` cannot be applied to type `core::iter::Map<'_,f32,f32,core::iter::Map<'_,&[f32],f32,core::slice::Chunks<'_,f32>>>`Performance

I added basic performance counters to Luculentus and Robigo Luculenta. It counts the number of trace tasks completed per second. These are the results:

| Compiler | Platform | Performance |

|---|---|---|

| GCC 4.9.1* | Arch Linux x64 | 0.35 ± 0.04 |

| GCC 4.9.1 | Arch Linux x64 | 0.33 ± 0.06 |

| rustc 0.12 2014-09-25 | Arch Linux x64 | 0.32 ± 0.01 |

| clang 3.5.0 | Arch Linux x64 | 0.30 ± 0.05 |

| MSVC 110 | Windows 7 x64 | 0.23 ± 0.03 |

| MSVC 110* | Windows 7 x64 | 0.23 ± 0.02 |

| rustc 0.12 2014-09-23 | Windows 7 x64 | 0.23 ± 0.01 |

Optimisation levels were set as high as possible everywhere. The compilers with asterisk used profile-guided optimisation. The only conclusion I can draw from this, is that you should probably not use Windows if you want performance from CPU-bound applications.

In the second post in this series, I noted that rustc compiles extremely fast, but there was very little code at that point. After the port, these are the compile times in seconds:

| Compiler | Time |

|---|---|

| rustc 0.12 2014-09-26 | 7.31 ± 0.05 |

| clang 3.5.0 | 13.39 ± 0.03 |

| GCC 4.9.1 | 17.3 ± 0.5 |

| MSVC 110 | 20.4 ± 0.3 |

No instant compilation any more, but still much better than C++.

Conclusion

Learning Rust was a fun experience. I like the language, and the port lead to a few insights that could improve the original code as well. Ownership is often implicit in other languages, which means it is prone to human error. Rust makes it explicit, eliminating these errors. Safety is not an opt-in, it is the default. This puts Rust definitely more on the ‘stability’ side of the spectrum than the ‘rapid development’ side. I have written not nearly enough code in Rust to make a fair judgement, but so far, Rust’s advantages outweigh the minor annoyances. If I could choose between C++ and Rust for my next project, I would choose Rust.

Discuss this post on Reddit.